“Can we now start talking about unemployment?”

—Paul Krugman

or almost four years now, we have argued back and forth on this blog about deficits and debts and jobs.

or almost four years now, we have argued back and forth on this blog about deficits and debts and jobs.

My position, and one that seems stunningly obvious to me, has always been that jobs and the economic recovery deserve precedence over debt reduction, even though long-term debt is a problem that has to be addressed.

For those of you who don’t follow Brad DeLong, the professor of economics from Berkeley, you are missing something valuable in the debate you see on television or read in the paper every day, almost all of that debate focused solely on deficit reduction. (Go here and read DeLong’s bona fides, if you think he’s just another liberal economist.)

Sunday, DeLong posted a blog entry with the title,

NO, WE DON’T REALLY NEED ANY MORE DEFICIT REDUCTION UNTIL 2020

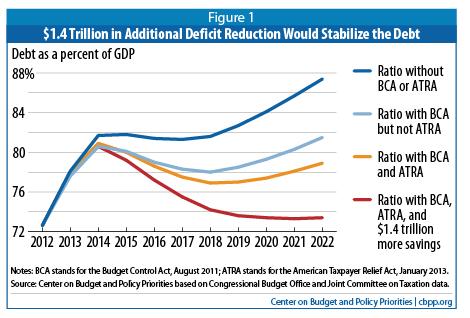

He borrowed from Paul Krugman, who borrowed from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (peer review?), this graph:

[Note: BCA is the Budget Control Act of 2011 (that “settled” the first debt-ceiling fight and which brought us the so-called fiscal cliff at the end of 2012) and ATRA is the American Taxpayer Relief Act, signed on January 2 of this year (the fiscal-cliff “settlement”).]

Here is Krugman’s description of the graph:

The vertical axis measures the projected ratio of federal debt to GDP. The blue line at the top represents the projected path of that ratio as of early 2011 — that is, before recent agreements on spending cuts and tax increases. This projection showed a rising path for debt as far as the eye could see.

And just about all budget discussion in Washington and the news media is laid out as if that were still the case. But a lot has happened since then. The orange line shows the effects of those spending cuts and tax hikes: As long as the economy recovers, which is an assumption built into all these projections, the debt ratio will more or less stabilize soon.*

Krugman makes the point that,

for the next decade, the debt outlook actually doesn’t look all that bad.

True, there are projected problems further down the road, mainly because of the continuing effects of an aging population. But it still comes as something of a shock to realize that at this point reasonable projections do not, repeat do not, show anything resembling the runaway deficit crisis that is a staple of almost everything you hear, including supposedly objective news reporting.

We know that most Beltway journalists have bought into the hype over deficits and debts, since that is just about all that Republicans want to talk about now that they aren’t in the White’s House. But the focus of congressional and presidential efforts in the short term should be on keeping the economy stimulated enough to really catch fire.

Brad DeLong offers this stinging rebuke of the President:

In focusing in 2013 on further deficit-reduction deals rather than on policies to boost employment growth and infrastructure investment, President Obama is making yet another hideous economic policy mistake.

Now, to be fair to Mr. Obama, he can’t entirely control the debate. He has constantly talked about the dangers of deep cuts in government spending and the need to keep the economic recovery going.

But he faces stiff opposition in Congress from austerity-drunk Republican teapartiers who are aided and abetted by an establishment press, a press that pushes on the public the weird idea that we are going to bleed to death if we don’t slit our throats now.

You figure it out. I can’t.

In the mean time, we need to stop worrying about the damn deficit for a while and start worrying, even exclusively worrying, about jobs and economic growth.

_______________________

* For budget geeks: About that red line on the graph above, the one that shows deficits leveling out as a percentage of the economy, that was the point of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities original piece, which explained it this way:

Achieving $1.4 trillion in additional deficit savings would stabilize the debt at about 73 percent of GDP by 2018. Some analysts prefer a lower debt ratio, such as 60 percent of GDP, a goal that the European Union and the International Monetary Fund adopted some years ago. No economic evidence supports this — or any other — specific target, however, and IMF staff have made clear that the 60 percent criterion is an arbitrary one. In addition, even if such a target were the best one before the recent severe economic downturn pushed up debt substantially in most advanced countries, it would not necessarily be an appropriate target for debt over the next ten years, given the severity of the downturn and continued economic weakness. The critical goal now is to stabilize the debt in the coming decade.

Herb Van Fleet

/ January 15, 2013As for me, I would rather go out with a bang than a whimper. Of course, going forward, raising the debt ceiling should not be a license for draconian spending cuts or for putting inordinately higher taxes on the middle class.

Under an opportunity cost analysis, a part of which you discuss above, and under the paradox of thrift doctrine (discussed elsewhere on this and Anson’s blog), I believe losses likely to be sustained through an austerity program are much, much higher than the possible gains. (See the United Kingdom and Greece.)

More than that, I would send the President to SCOTUS to have this whole debt ceiling sham declared unconstitutional. Congress cannot incur expenditures and then turn around a refuse to pay those legally binding (?) obligations. (I think the word is “honor.”) It would be interesting to see the right-leaning justices try to ignore their beloved 14th amendment. But then, they did give us Citizens United didn’t they. R-Uh R-Oh.

Herb

LikeLike

ansonburlingame

/ January 15, 2013Com’on Herb,

Congress authorizes spending each and every year AND authorizes borrowing. It works the same way, privately. I may go buy a car, last year, with every intention of paying for it over time. But then “something happens” and I don’t have the money to keep making payments on the car. I have several choices, all reasonable ones. I can borrow the money to continue to pay for it, or sell it and pay it off, or let the “bank” take it away from me, etc., etc.

What I can’t do is make some “plea” that I “need” the car and therefore get other people to pay for it for me!!! Bicycles and motor scooters are always an option.

Businesses do so all the time. It is called, in business and for individuals, ones “eyes being bigger than their beak” (applies to pelicans,etc.)

But that is not really why I comment here. My point is simple, Duane. ALL the curves have a common “assumption” a HUGE assumption. That is that the economy WILL “recover”.

But I see no explanation of the definition of “recover” anywhere as the basis for all those curves. Specifically, what is the assumed rate of growth in GDP that is the common basis of all those curves? Make that assumption high enough and any of those curves can be made to “look just fine”.

Along with that point, here is a second one. My “guess” is that no additional “big spending programs”, new programs, are assumed in any of those graphs. Rather they take the first projection and simply “wack off” numbers assumed to be gained in spending reductions and tax increases based on current laws (with or without BCA, ATPR, etc.) I also bet that “little things” ($60 Billion for Sandy, the “pork” in the recent bill, etc.) are not included in projections.

All the curves assume, I suppose, that proposed, future spending cuts in current agreements will remain unchanged. So ten years from now we can all safely assume that some “small” cut in spending agreed to in 2011 will in fact be inviolate in ten years when the cut really happens. Hmmmm?l Hell we can’t trust Congress in ONE year, much less the out years!!

Finally, we cannot even agree of the definition of “debt”. I take the position that if we owe it legally, it is a debt. The left hand ordinate in the graph is “debt held by the public” which I have long argued against using as the norm for our real debt, total money legally owed by the federal governent, interagency, public or “over there”. As well don’t try to discount that total debt with the “assests” held by the government. I say so because I doubt we will ever “sell the capital building” to pay down the debt!! The percentages should be in the 120% range, not 60-80% in my view.

Anson

LikeLike

Herb Van Fleet

/ January 15, 2013Anson,

I see your argument and tend to agree with it. But government is not a individual or a business enterprise. You may borrow money to buy the car, but government borrows money to build the road it travels on. And the reason the government had to borrow that money is because our elected representatives thought it OK to spend more than it takes in. It’s the tyranny of the majority at work, and politics at its worst.

Elected officials want to be re-elected. So, they treat the U.S. Treasury like a candy store; handing out treats willy nilly to their constituents; tax breaks for the rich, entitlements for the poor. Over time this creates some considerable mischief in our economy. Something like we’re seeing now. As I’ve said many times before the behavior of Congress is irresponsible, indefensible, dishonorable, and, by posing a real threat to this nation’s financial health, unpatriotic, if not outright treasonous.

Churchill said that democracy is the worst form of government there is except for all the others. One wonders if today Churchill migh add our version of democracy in with the “others.”

Herb

LikeLike

ansonburlingame

/ January 16, 2013Herb (and probably others)

We AGREE! You said, “It’s the tyranny of the majority at work, and politics at its worst.”

Spending more than we make, over a long period, is exactly such. As well if the GOP held power today we could well cut spending to the point that people would be “starving in the streets”. And both situations could easily be the “will of the majority” but never the real “will of the people”.

My wife and I saw Les Mis yesterday. She loved it and I did not. I thought the stage play and real professional musicians (as opposed to great actors) was a much better rendition of perhaps the best musical ever performed. But that is just a comment on a movie. It was Janet’s question afterwards that struck a cord with me. She is not familiar with the real lessons from the French Revolution and we discussed it over hamburgers after the movie.

My point was the French Revolution, unlike the American one, was internal class warfare, rich vs poor in France. And ultimately it failed. I then suggested that the Russian Revolution 100 years (or so) later had the same basis, class warfare within a country.

I then asked her what might happen if OWS mobs in America had their way. To me it would be akin to the French and Russian revolutions and a far cry from our own in America, a whole country of people united against a foreign threat. Anyone could easily make a movie or stage play glorifying an “OWS revolution” with “poor people” waving flags and singing great songs, inspirational songs. But “It’s the tyranny of the majority at work, and politics at its worst.” is it not?

Anson

LikeLike